Japanese Landscapes @ the Clark

Thursday, December 20, 2012

We arrived just a few minutes past 1:00 pm on Saturday, just a little late to catch the beginning of the weekly docent tour. Our three doubled the audience to six as Sonja Simonis, curator of this exhibit, talked about the individual artists, the 29 landscapes on display, and the represented traditions and influences, especially as the Japanese adapted what they learned from the Chinese. The Clark Center invites young scholars for assistant curatorial internships, and Simonis is the 18th intern in thirteen years. She told me she did most of her studies in Berlin, but researched her thesis in Japan.

The collection goes back into the 15th Century, and some of the commentary refers back to about the 10th. Several traditions are represented: Zen priests who painted as a path to enlightenment; Daoists who painted as a path back to nature and tranquility; bunjin, or literati, men of letters who painted as a pastime and to share with their friends; and professional painters who decorated castles for the Shoguns and Daimyo.

One of the oldest pieces, Mountains by a River, is attributed to Kenkō Shōkei (active about 1478-1506), a Zen priest who studied paintings from Song and Yuan China. In the Zen tradition, landscape paintings—usually of fictitious locations—served as meditative devises.

|

| Detail from Mountains by a River, a matching pair of hanging scrolls, attributed to Kenkō Shōkei. Ink and color on paper. |

|

| Winter Landscape (above), with detail (below), by Kanō Tan’yū (1602-1674). |

,+Priest+Looking+out+into+a+Snow-covered+Landscape.JPG) |

| Itaya Keishū (1729-1797), Priest Looking out into a Snow-covered Landscape, hanging scroll, colors on silk. |

|

| Detail from, Priest Looking out into a Snow-covered Landscape. |

When I looked closely at Landscape after Dong Yuan, by Nakabayashi Chikutō (who predates the opening of Japan), I was struck by its near-Pointillism, a technique I associate with late 19th Century, European Impressionists.

|

| Landscape after Dong Yuan, by Nakabayashi Chikutō (1776-1853). |

Nakabayashi served as a Nanga theorist, painting and writing in Kyoto.

Mizuta Chikuho (1883-1958) taught painting and frequently served as a judge in art exhibitions. In Fairly Unsettled Weather (1928), a figure in a blue kimono looks out from the window, the painting’s only deviation from a shades-of-gray color scheme.

|

| Fairly Unsettled Weather (1928), with detail at right, by Mizuta Chikuho. Ink and light colors on paper. |

|

| Plum Blossom Library (1926), with detail at left, by Fukuda Kodōjin (1865-1944). Ink and colors on silk. |

Spring breezes fluttering the lapels of my robe.

With just this peace my desire is fulfilled, while the world’s affairs leave me at odds.

White haired but not yet passed on,

These green mountains a good place to take my bones.

Who understands that this happiness today lies simply in tranquility of life?

(trans. Jonathan Chaves)

Color and detail also attracted me to Komuro Suiun’s Mount Hōrai. A contemporary of Kodojin, and another Daoist painter of the Nanga School, this painting pictures the palace of the Daoist Eight Immortals, who live in a place without pain or sorrow. Near the inscription, a flock of crains symbolize luck and long life.

|

Mount Hōrai, with detail on right, by Komuro Suiun (1874-1945). |

|

| Twenty-four feet from the 72-foot long of Hekiba Village, by Araki Minol. |

|

| Detail from Hekiba Village, by Araki Minol. |

In this video, I attempt to catch the sweep of Hekiba Village.

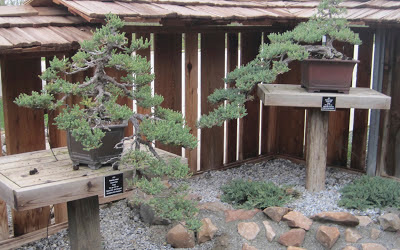

One final thought: Beside the art gallery, the Clark Center has a bonsai garden, and this has recently been redesigned to better show-off the collection.

(My review of a previous exhibition at the Clark)

Posted by

Brian

at

10:56 AM

3

comments

Labels: California, China, Garden, History, Japan, Museums, Travel

Lamentation of a Parent, Grandparent, and Teacher

Saturday, December 15, 2012

I took this picture during a school lockdown in 1994. In Colombia, unidentified soldiers had stepped out of the jungle within a mile of the school, so we locked down until we could be sure for whom those soldiers fought. My junior high students sat for two hours before the all-clear, joking nervously and missing lunch. But we were in a war zone. There, one understands—at least intellectually—that violence is a possibility.

In California, I once locked down with 4th graders while a funnel cloud just missed us. Before terrified ten-year-olds, the teacher must be strong, even casual about the situation, and compartmentalized. But now, even during our school’s annual lockdown drill, I have to stop and consciously gain control over the catch in my voice.

So it is good that I first saw news of the Sandy Hook shooting while I was alone in my classroom during lunch. As a teacher, a parent, and a grandparent, I cried. Then I compartmentalized, taught my afternoon classes, and went home to let my four and six-year old grandsons present me with an early-birthday batch of raisin cookies. Today, I will celebrate that 63rd birthday with a museum trip, and intellectualize.

The violence is common enough—even in elementary schools and movie theaters—that we have rituals for dealing with it.

One group of us divides into Pro-Gun and Anti-Gun factions. That is a debate we ought to have, though probably less driven by the most immediate atrocity. Prudence and self-defense may require that some citizens keep guns, but from scripture I draw the principle that trust in weapons is misplaced (Isaiah 31:1 and 2:7), and the glorification of weapons is idolatry. I waver over where to draw the legal lines on guns, but as a nation we trust and glorify them,. For trusting and glorifying, the lines should be at zero.

Another group points to lack of mental health, to the breakdown of the family, to a culture of violent video games, and to hopeless poverty. Yes, yes, yes, and yes. Every year I see students who are in need of better help than the schools are equipped to handle. I see boys—especially—trying to understand manhood when they have no fathers with whom to relate. This very week, I had several boys excited to show me videos that glorified lone attackers who vanquished large armies. I also just heard the verdict on a shooting a few years ago in the park around the corner from where I live. A lone gunman sprayed bullets into a pick-up soccer game, wounding one player. Charged with 10 counts of attempted murder, he received 500-years-to-life. The shooter was 16. Fatherless. Without a DREAM Act, he was also a boy without a country, and no hope of ever belonging anywhere. Except to a street gang.

Yet, curiously, the shooters in mass killings like that at Sandy Hook or in Aurora have been mostly white, middle class, and American born; as have been their victims. The other kind of shootings, kids killed one or two at a time as some gang initiate tries to prove his mettle, probably claim more victims in total, but make fewer headlines. The spontaneous monument in the photograph below sprang up after three boys were attacked in a yard across the street from where I pick up kids for Sunday school. One seventeen-year-old died. He had been a friend of the kids I pick up. The young shooter, who received a life sentence, was a recent alumnus of the school where I teach. Easy guns. Video games that glorify the lone shooter. Hopelessness and lack of belonging. Spiritual deadness. Isolated, one from this list does not create shooters, but together, they will.

So to cope with this, we compartmentalize. We intellectualize. We blame-shift. We look the other way that our drones are killing children in Afghanistan and Pakistan. We try and hide the fact that, each year, a million American children are denied even a day of birth. We flee from the knowledge that the stores we frequent support firetrap-sweatshops in Asia or Latin America, and that the chocolate we eat was harvested by child slaves in Africa. We have met the evil, and it is us.

Psychically we cannot carry these burdens, individually, or as a people. It is too heavy. We try to imagine ourselves standing in the way of all this, correcting it, or even absolving ourselves of our complicity in any of this, and we can’t. It is too overwhelming.

But it is not too heavy for God.

And God hears our cries.

I am driven this morning to read Daniel 9:4-19, and to use his prayer as my model.

4 I prayed to the Lord my God and confessed and said, “Alas, O Lord, the great and awesome God, who keeps His covenant and lovingkindness for those who love Him and keep His commandments, 5 we have sinned, committed iniquity, acted wickedly and rebelled, even turning aside from Your commandments and ordinances. 6 Moreover, we have not listened to Your servants the prophets, who spoke in Your name to our kings, our princes, our fathers and all the people of the land.

7 “Righteousness belongs to You, O Lord, but to us open shame, as it is this day—to the men of Judah, the inhabitants of Jerusalem and all Israel, those who are nearby and those who are far away in all the countries to which You have driven them, because of their unfaithful deeds which they have committed against You. 8 Open shame belongs to us, O Lord, to our kings, our princes and our fathers, because we have sinned against You. 9 To the Lord our God belong compassion and forgiveness, for we have rebelled against Him; 10 nor have we obeyed the voice of the Lord our God, to walk in His teachings which He set before us through His servants the prophets. 11 Indeed all Israel has transgressed Your law and turned aside, not obeying Your voice; so the curse has been poured out on us, along with the oath which is written in the law of Moses the servant of God, for we have sinned against Him. 12 Thus He has confirmed His words which He had spoken against us and against our rulers who ruled us, to bring on us great calamity; for under the whole heaven there has not been done anything like what was done to Jerusalem. 13 As it is written in the law of Moses, all this calamity has come on us; yet we have not sought the favor of the Lord our God by turning from our iniquity and giving attention to Your truth. 14 Therefore the Lord has kept the calamity in store and brought it on us; for the Lord our God is righteous with respect to all His deeds which He has done, but we have not obeyed His voice.

15 “And now, O Lord our God, who have brought Your people out of the land of Egypt with a mighty hand and have made a name for Yourself, as it is this day—we have sinned, we have been wicked. 16 O Lord, in accordance with all Your righteous acts, let now Your anger and Your wrath turn away from Your city Jerusalem, Your holy mountain; for because of our sins and the iniquities of our fathers, Jerusalem and Your people have become a reproach to all those around us. 17 So now, our God, listen to the prayer of Your servant and to his supplications, and for Your sake, O Lord, let Your face shine on Your desolate sanctuary. 18 O my God, incline Your ear and hear! Open Your eyes and see our desolations and the city which is called by Your name; for we are not presenting our supplications before You on account of any merits of our own, but on account of Your great compassion. 19 O Lord, hear! O Lord, forgive! O Lord, listen and take action! For Your own sake, O my God, do not delay, because Your city and Your people are called by Your name.”

Posted by

Brian

at

8:56 AM

4

comments

Labels: Abortion, Bible, Christian Worldview, Colombia, Former Students, Grandparenting, Lomalinda, Memoir, Teaching

Escapade @ Qasr al Yahud

Saturday, December 01, 2012

Last night at our Bible study, I was deep into recounting an

old adventure, when I realized it was exactly 40 years old, this past

week. So today, I searched the Internet

and answered questions I’ve carried with me for two-thirds of my life.

Our study had looked at Moses and the Hebrews in the desert,

as Yahweh had brought His people out of Egypt, but now intended to refine Egypt

out of His people. Then our leader

asked, “Does anybody have a desert experience they would like to share?

In Christian parlance, the term ‘desert experience’ usually

means a dry time in our lives when God works important changes in us. My story was far more literal.

|

| My future wife and my mother, seeing me off at LAX as my trip began, September, 1972. |

At Thanksgiving time, 1972, I found myself in Israel,

without much forethought. I had been

hitchhiking through Europe, with a goal of reaching Istanbul in time to mark my

ballot. I had missed voting in 1968,

when it was restricted to 21-year-olds.

Then the Twenty-Sixth Amendment gave even 18-year-olds the right to

vote, and at 22, I intended to cast my ballot for George McGovern. Sitting at the US Embassy at The Haag, I had

taken a leap in the dark, and asked for my ballot to be mailed to Istanbul.

A week later, after a visit to East Berlin and returning to

the West, on a sidewalk in Braunschweig, I had what Christians

sometimes refer to as a ‘Damascus Road Experience.’ I went into it as an agnostic, and

came out a few minutes later as a servant of Jesus Christ.

One week after that, I sat in a student-travel office in

Basel, Switzerland, trying to figure out how—once I had reach Istanbul—I could

get back into Western Europe. They

offered a cheap flight from Tel Aviv to Rome.

On the map, Israel and Turkey look close. How hard could it be to get from one to the

other?

These are all stories I will need to tell sometime, but what

is pertinent here is that during Thanksgiving week, I found myself in the

Jerusalem Youth Hostel, carrying a much-diminished cache of traveler’s checks,

but thinking I would like to take the bus down to Jericho. (I will point out that I have no photographs

of my own from this portion of my trip, because I couldn’t spare the shekels

for a roll of film. Thank you,

Wikipedia, for the use of yours.)

.jpg) |

| Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, where I did spend some time. Photo by Alex S at en.wikipedia, from Wikimedia Commons |

A Jewish kid from San Francisco decided to join me, and so

one morning we walked to the bus station.

Had I known, right behind that station is a rocky escarpment bearing

Gordon’s Tomb, believed by many to be a more likely spot for Christ’s burial

and resurrection than the traditionally recognized Garden Tomb. However, at the time, I didn’t know, and so

didn’t walk around behind the building to take a look.

| Golgotha, the Garden Tomb, or "Gordon's Calvary," which I did not know to look at when I was at the bus station. Photo by Footballkickit at en.wikipedia, via Wikimedia Commons |

The journey through the Judean Hills doesn’t take long, and

is interesting. It follows the path on

which the Good Samaritan came to the assistance of a man who had been beaten by

robbers, and innumerable other Biblical accounts.

Once through the mountains, we could see the Dead Sea, in

the distance, though we did not make that side trip. The bus stopped once, so that a Palestinian

woman with a live chicken under each arm could disembark, though no buildings

were in sight. We probably pulled into

Jericho about 10:00 or 11:00.

There wasn’t a lot to see.

I remember one very attractive house, with a beautiful veranda of Bougainvillea. There were some citrus orchards, and date

palms. There were archaeological

diggings that one could visit for only a pittance, but I could spare not even

the pittance.

|

| Archaeological diggings at Jericho, which I did not get to see. Photo by By Abraham at pl.wikipedia, from Wikimedia Commons |

So I studied my map and realized it could not be more than

six miles to the Jordan River. At three

miles an hour, we could be there and back in time to make the last return bus to

Jerusalem, at 4:30.

| |

| Map based on http://wikimapia.org/#lat=31.8451463&lon=35.5019931&z=15&l=0&m=b |

My friend was opposed to the idea. The river was, after all, the border between

two countries that now-and-again shot at each other. I knew this.

I recognized we might not get all the way to the river, but I was going

as far as they would let me. He could

either join me, or head back to Jerusalem on his own. He decided to come.

So we set out, with the land becoming more barren as we

walked, and my friend complaining all the way.

I believe it was the same for his ancestors who accompanied Moses.

By the fifth mile, the landscape had been come steep hills

of soft sand, with some dry weeds in the gullies between them. My friend was afraid we would not be able to

get back to Jericho in time for our bus, and that we would be stuck in the

occupied West Bank over night, at the mercy of the Arabs. It was getting late.

But up ahead, there was a building. We could go just that far, I told him, and

ask for a drink of water. Then we would

go back. He agreed. As we approached the building, I noticed what

appeared to be a periscope rising from the sand, following our movements.

| Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, at Qasr al Yahud, photo by צילום:דר' אבישי טייכר, via Wikimedia Commons |

From Google Maps, I now know that the building was a Greek

Orthodox monastery, Saint John’s, and that only a third of a mile separates it

from the Jordan River and the spot traditionally believed to be where John the

Baptist baptized Jesus (though Jordan and Israel differ over whether Jesus

stepped in from the Jordanian or Israeli side).

Some traditions also name it as the spot where Joshua and the Hebrews

crossed the Jordon on their way to attack Jericho. Also, somewhere very near is the spot where

Elijah departed for heaven in a chariot of fire. At the time, none of this occurred to me, and

I recognized only that the monastery was some ethnicity of Orthodox. I also couldn’t see that just beyond the

monastery, the desert fell away rapidly to the lush bed of the Jordan.

We knocked, and the only man we saw inside got us water that

tasted of too much time in cheap plastic containers, but we were thirsty. Then the monk asked if we would like to see

the chapel. I did, though my complaining

friend did not, so I followed the monk into a small-but-dazzling room, so full

of art, icons, candled chandeliers, and mosaics that I could not take it all

in, and dared not take the time to do so.

In gratitude, I left a few coins in an offering plate, truly a widow’s

mite, but probably more than would have been the admission to the

archaeological digs.

We stepped outside to find three Israeli soldiers examining

our foot prints. They insisted that

there were three sets of prints, and wanted to know who the third person had

been. What could we say? There had never been any but the two of us.

Eventually, they accepted that, but by now it was getting

seriously late. Would they give us a

ride back to the highway so we could catch the bus? They consented, and we jumped in the back of

their pickup truck. They also had a

Jeep-type vehicle, which was good, because the truck quickly got stuck in soft

sand, and came close to rolling down the side of the hill. We jumped out.

The soldiers tried racing the wheels, but the truck simply

dug itself deeper. Then they backed the

other vehicle in front of it, and tied a thin hemp rope between the

bumpers. I tried to squelch a

laugh. Did they really think that would

hold? Apparently they did, though of

course it failed, twice, actually.

Finally, they took the other vehicle down into the gully and brought it

up behind the truck. That was

impressive. I never could have imagined

a vehicle coming up that hill in the soft sand.

But they couldn’t get the truck to budge. They decided to abandon the truck to the

Arabs and the night.

The five of us crowded into the Jeep, and they drove. But shortly the soldiers began arguing among

themselves. They stopped, took their

map, and walked to the top of a hill, making it quite obvious they were lost. Was this the army that only five years

earlier had beaten the combined armies of Islam in only six days, outnumbered

thirty-to-one? (And they would, within a

year, need only three weeks to repeat the feat.)

The soldiers dropped us off beside the highway, with about

fifteen minutes to spare before the bus came by. By my birthday, in December, I was back in

England, and by Christmas I was in California.

By the end of January, I was engaged, and by July I was married. I did not have a lot of time to ask questions

about what I had seen.

But today, I poked around on the web. Bouncing between Google maps, Google search, and Wikipedia, it was pretty easy to settle on Saint John's Monaster (Kasser, or Qasr, Al-yahud), and to realize how close I'd gotten to the Jordan River. At the time, Israel forbid access from its

bank, though I don’t know how much closer I might have gotten. We’d stayed on a dirt road, but if we had

drifted too far into the fields, we might have encountered land mines. (Americans go blithely, where even fools may

fear to tread.) Today, both countries

allow access to the baptismal site, and I know people who have visited there.

Someday, I would like to visit Israel again, and should that every happen, I will go better prepared to understand what I am seeing. But that will not take away from the adventure that Israel was the first time I was there.

In the meantime, I pray for Peace in Israel. I once rode with the Israeli army.

In the meantime, I pray for Peace in Israel. I once rode with the Israeli army.

Posted by

Brian

at

11:29 PM

5

comments

Labels: 1972, Bible, Christian Worldview, History, Israel, Memoir, Travel

Why I Will Vote to Repeal the Death Penalty

Saturday, October 13, 2012

On November 6th, I will vote in favor of

California Proposition 34, to replace the death penalty with life in prison

without possibility of parole.

Some people will vote for Prop 34 because a financially

strapped California cannot afford a death penalty that costs $185,000 per year more,

per convict, than housing that same convict for life. If California’s 725 condemned prisoners were

integrated into the general prison population, it is also likely the state

could sell its antiquated San Quentin prison, which sits on prime San Francisco

Bay real estate, and replace it with a modern facility on cheaper land,

somewhere else in the state. The

financial arguments for Prop 34 are sound, even if they are not the primary

reasons for my support.

Some people will vote for Prop 34 because a financially

strapped California cannot afford a death penalty that costs $185,000 per year more,

per convict, than housing that same convict for life. If California’s 725 condemned prisoners were

integrated into the general prison population, it is also likely the state

could sell its antiquated San Quentin prison, which sits on prime San Francisco

Bay real estate, and replace it with a modern facility on cheaper land,

somewhere else in the state. The

financial arguments for Prop 34 are sound, even if they are not the primary

reasons for my support.

Some people will vote for Prop 34 because of evidence that we

have executed innocent people. The

recently available DNA tests have exonerated many condemned prisoners, and

those exonerations call into suspicion a percentage of the rest. Even one such execution would be too

many. It is also evident that a

disproportionate number of the condemned were poor, marginally educated, and/or

persons of color. I accept these as

worrisome aspects of our current law.

Some people will be impressed by the list of leaders who

support repeal. Jeanne Woodford presided

over 4 executions as Warden of San Quentin State Prison. Donald J. Heller wrote the wording for the

1978 law (Proposition 7) that established our current death penalty, and Ron

Briggs led the successful campaign to get it passed. John Van de Kamp was Attorney General of

California from 1983-1991. Antonio R.

Villaraigosa is the current mayor of the City of Los Angeles. Carlos Moreno voted to uphold about 200 death

sentences in his time on the California Supreme Court, defendants who he says,

"richly deserved to die." But Moreno supports Proposition 34, because

"there’s no chance California’s death penalty can ever be fixed.” I am not a band-wagon kind of guy, but it is

an impressive list.

I do not even support Prop 34 because

of a personal friendship with one of those 725 inmates on San Quentin’s Death

Row. My interest in the death penalty

goes back to the 1960 execution of Caryl Chessman, when I was in the 4th

grade. I have now spent 52 years

thinking on the subject, read dozens of books, sat down with the assistant

warden who supervised Chessman (“He was the most evil man I ever met.”), and

made it a central theme of the novel I can’t find the time to finish. About ten years ago I began a pen-pal

relationship with a serial killer who had already been on Death Row about eight

years. Twice, I have been to San Quentin

to be locked in a visitor cell with him.

The reports are that the 725 people who will be most affected by Prop 34

hope it won’t pass. (As convicted felons,

they don’t get to vote.) They know that

more Death Row inmates die of old age than of lethal injection, and that Prop

34 would deny them their roomier cells, and dump them in with the general

population. As my serial-killer friend

told me, “This place is full of some really scary people.”

All of these are good reasons to vote

for Prop 34, but my own reasons are Biblical.

In this I have reached a very different conclusion than many of my

Christian brethren. I have grown to

accept a line of argument in the Mennonite tradition, though I am not,

otherwise, Anabaptist in my theology. In

this, I am most indebted to Against the Death Penalty: Christian and Secular

Arguments against Capital Punishment, by Gardner C. Hanks (1997).

Most Christians see the primary

instruction on capital punishment as coming from God’s commandment to Noah

(Genesis 9:6), “Whoever sheds man’s blood, by man his blood

shall be shed, for in the image of God He made man.” However, this is neither the first nor the

last statement by God on the subject.

When the world’s first murder occurred (Gen. 4:8), God invoked

banishment as Cain’s punishment. Cain

protested that this would put his own life in jeopardy, and God pronounced a

seven-fold judgment against such vengeance.

As we analyze what we hope to accomplish by Capital Punishment, it had

better not be vengeance, because God reserves vengeance as His right, alone

(Rom. 12:19). For one thing, it is

always human nature to take vengeance beyond even what God may have sanctioned. By the end of Genesis 4, a fellow named

Lamech is bragging, “If Cain is avenged sevenfold, then Lamech

seventy-sevenfold.”

It is in the context of just such

violence (Gen. 6:11) that God chooses to end the cycles of vengeance by wiping

out the violent. He will start over with

Noah. God’s first choice for dealing

with murder was banishment, but man could not live up to that plan. So in order to prevent such cycles of revenge

killings, God issues His second-choice, the commandment in Gen 9:6. God is extremely concerned to have peace

within mankind’s communities.

In the New Testament, Jesus does not

speak often of murder, but when he does, he convicts us all, “But I say to you that everyone who is angry with his brother

shall be guilty before the court; and whoever says to his brother, ‘You

good-for-nothing,’ shall be guilty before the supreme court; and whoever says,

‘You fool,’ shall be guilty enough to go into the fiery hell.” (Matthew

5:22)

Curiously, when Jesus goes to the

cross, the most immediate beneficiary is Barabbas. A condemned murderer, in a one-for-one

exchange, Jesus died in his place and Barabbas walked free (Matthew 27, Mark

15). In faith, I believe that Jesus died

for my sins, as well, but even those without faith can see how Jesus died in

place of Barabbas. After the

crucifixion, every subsequent execution in the Bible is for being a Christian.

I believe a sentence of life in prison

serves as the banishment that was God’s first choice for murderers. Life without parole serves God’s interest in

protecting society and in forestalling cycles of retaliation and

vengeance. Within the idea of justice, there

is the further sense that a crime has knocked things out of balance, and that

someone must pay in order for there to be a return to balance. This is the requirement that often calls for

the perpetrator to suffer execution. But

my theology tells me that Christ died to supply that return to balance. There are earthly requirements for the

purpose of restitution or for protecting society, but my theology tells me

Christ died to restore the cosmic balance for the debt of all sin. He also died in hope that no human soul

should ever have to enter hell, and that none is so far gone as to be beyond

salvation.

I believe, when I was visiting my

friend on Death Row, that I recognized guards escorting David Westerfield to a

visitor’s cell. Some readers, just

seeing his name, will experience anger.

To call him “good-for-nothing” or “fool” hardly seems strong

enough. Yet Jesus tells me I jeopardize

my own soul for thinking such thoughts.

I believe it works like this: Hell is a place intended primarily as a

punishment for Satan and his demons. Though

souls who reject God will go there, it has always been God’s hope that none

would ever do so. The reality of Hell is

so horrible that we humans should never wish it on any fellow human, no matter

how heinous their crimes. Rather, we

should hope and pray for every soul, right up until the time when God, in His

sovereignty, takes that person’s life.

Vengeance is His. The timing is

His. Life without parole protects

society, and I will vote for Prop 34.

Posted by

Brian

at

11:07 PM

5

comments

Labels: 2012 Elections, Bible, California, Christian Worldview, Friday 10:03, History, Politics

TRUE BLUE: Reviewing a ten-year-old book

Sunday, July 29, 2012

TRUE BLUE: The Dramatic History of the Los Angeles Dodgers,

Told by the Men Who Lived It

by Steve Delsohn

·

Paperback: 320 pages

·

Publisher: Harper Perennial (2002)

· ISBN:

0380806150

I am a Dodger fan, though I look at the current roster and

recognize only the names of coaches Manny Mota (a Dodger since 1969) and Davey

Lopes (who joined the team in 1972). My

emotional investment runs to the Walt Alston line-up of my childhood; the Sandy

Koufax, Don Drysdale, and Maury Wills Dodgers of the late ‘50s and early-to-mid

‘60s.

This summer, I have been reading a wide range of California

history, including two books on the Dodgers.

Roger Khan’s delightfully literary, THE BOYS OF SUMMER, focuses mostly

on the Brooklyn Dodgers of the early ‘50s.

Those same players formed the core of the team that I remember coming to

LA in 1958: Duke Snyder, Jim Gillium, Wally Moon, Johnny Roseboro, and Pee Wee

Reese. Delsohn’s TRUE BLUE dips back

into the Brooklyn years only enough to set the stage for that move. Then, year-by-year, he uses interviews to

record the memories of the players and close observers who made up the Dodger

teams until the close of the century.

That pretty much chronicles the baseball years of my

life. I was eight when the Dodgers

arrived in LA. In 1959, I attended my

first professional game, Dodgers vs. Cincinnati, in the Coliseum. For the next decade, I didn’t make it to the

bleachers very often, but I listened to most games on the radio, and checked

box scores every morning in the LA times.

By necessity, a history of fifty years—both on and off the

field—can hit only the high points, and most fans will want to offer their own

list. Yet Delsohn hit all but two of

mine. His quick overview of the

politics behind the new stadium at Chavez Ravine missed the bitterness of the

community that lost their homes. I could

only have been ten, but I remember the standoff between police and a man armed

and barricaded in his home, while the bulldozers stood ready to demolish

it. Throughout my teaching career, I

have gone back to that illustration every time I needed to explain the workings

of eminent domain.

I also would have included Dick Nen. Delsohn recalls the pennant drive in 1963,

clinched when the Dodgers swept a series in Saint Louis. I remember Nen’s homerun in that series, the

only hit he ever had as a Dodger, tying a game they went on to win. Nen came up from the minors late in the

season, and was traded at season’s end to the American League. I remember standing on the playground at

school, listening on a radio. Curiously,

all these years later, I remembered it happening four years earlier, the year

the Dodgers beat the White Sox in the World Series, and my memory had me listening

to it on a different playground. Our

minds play tricks on us, and reading history helps set us straight.

In childhood, these Dodgers were my elders—two and three

times my age—and heroes. It is

interesting now, at age 62, to look back at them as young men, half, or even a

third my age. Koufax conquered the

world, and retired at 30, almost like Alexander the Great.

I must have been about twelve when I stood in line an hour

at a bank opening, to stand in front of Koufax for a few seconds while he

signed his name to a plastic bat and handed it to me. What finally became of that bat, I don’t

know. We were kids. We thrashed it hitting tennis balls in the

street, the closest we ever got to real baseball. A rolled up newspaper was the pitcher’s

mound, and I was Sandy Koufax staring down Mays or McCovey. Never mind that I threw right handed, at a

velocity that barely overcame inertia, and my opponent was a brother three

years my junior. And we were appalled when

Koufax retired.

That 1966 season he’d gone 27-9, with an ERA of 1.73.

Forty-six years later, I can view the

retirement in a very different light. I

have my own bum knee, earned at age 17, while trying to push my body beyond

what it could reasonably do. The team

doctor had warned Koufax before the 1966 season that pushing his arm could

leave him permanently crippled. Delsohn

also suggests the intensely private Koufax had been humiliated during the

previous winter’s salary negotiations.

Stingy Walter O’Malley had belittled Koufax in the press for several

months, before finally raising his annual salary from $90,000 to $125,000.

The book also probes the motivation for

Koufax’s refusal to pitch the opening game of the 1965 World Series, because it

fell on Yom Kippur. Previously, Koufax

hadn’t displayed enough religious devotion to justify such a decision, but

Delsohn concludes that Koufax took seriously his position as a role model to

thousands of youngsters. That is the

stuff our sports heroes ought to be made of.

The 1972 season started with the first

Major League Players’ Strike, and ended for me in September, when I left for

Europe. It was impossible to catch Vin

Scully’s radio-casts while hitchhiking through foreign lands. Only in December did I learned who won the

Series (Cincinnati). I’d broken my

childhood addiction, cold turkey.

On the other hand, in 1973, marriage

brought me a father-in-law who bought Dodger season tickets. That brought me a very different relationship

with the Dodgers. The Ron Cey, Bill Russell,

Davey Lopes, and Steve Garvey Dodgers were my own age, peers rather than heroes

for daydreams. As Delsohn’s book moved

into the Tommy Lasorda years, I was surprised to still recognize the names of

every player.

That didn’t change until the teams of

the mid 1980s. By then I was overseas

again, this time in the wilds of eastern Colombia, teaching school on a small

Bible translation center. Delsohn

doesn’t mention Karis Mansen, but he should have. Karis became my conduit to the Dodgers. By day, she was a linguist, translator, and

mother-of-three. But in the wee hours of

the morning, she tuned into Armed Forces Radio to catch her Dodger games. Then she would keep me posted. The 1985 season stands out in my memory. Near the All Star break, Karis told me the

team was in fourth, several games below .500.

I figured the season was over, and didn’t ask again until October. A very animated Karis told me the Dodgers had

taken their division, and would be facing Saint Louis in the play-offs. They had, she said, turned it around.

I no longer follow baseball, and beside Mota and Lopes, can

only name two active major leaguers (Diamondback Aaron Hill attended our church

when he was small, and Astro’s manager Brad Mills is a former neighbor).

But that was not the case 50 years ago, and as Delsohn wove

together interviews of players and others near the game, it took me back to a

time when I rarely missed a game on the radio, or a box score in the next

morning’s LA Times. He refreshed

memories and filled in gaps in my knowledge.

He even supplied the missing pieces for some mysteries I’d carried since

elementary school.

These days, I may not often think about baseball. But when I do, I think Dodger Blue.

A previous Dodger post, The Back of Duke Snyder's Head, is from Feb 28, 2011.

The link on this screen saver is here

Posted by

Brian

at

9:09 PM

2

comments

Labels: Anecdotes, Baseball, Books, California, Colombia, Europe, Famous People, History, Lomalinda, Memoir, Sports, Travel

Kamisaka Sekka and Rimpa/Rinpa @ the Clark

Monday, May 28, 2012

| ||

| Opening day for Kamisaka Sekka |

It shouldn’t happen, but it had been

twenty-seven months since I last visited the Clark Center for Japanese Art and

Culture, even though it is only a bare twenty-eight miles from my door. I was very aware of missing several

interesting exhibitions, and my only excuse is busyness. So earlier this month, I stole an afternoon I

didn’t really have, and went to see the opening of Kamisaka Sekka, 1866-1942: Tradition and Modernity (running through

July 28). In truth, the presentation

goes far beyond this one artist, and gives a history of the Rimpa School (琳派 Rimpa or Rinpa), of

which Kamisaka was its last great master.

|

| Detail from Kusunoki Masashige before the Battle, Kamisaka Sekka (ca. 1918) |

I have long been intrigued by most

things Meiji. It astounds me that a

nation could—by an act of will—redefine itself so quickly. Japan leaped from 17th Century

feudalism to 20th Century modernity in barely half a century. It made an art of copying Europe and America

in major areas of life, and yet managed to accomplish its leap with most of its

national character intact. Compared to,

say, a similar effort in China under Mao Zedong, it was almost bloodless, and

so much smoother.

|

| Kamisaka Sekka |

Kamisaka Sekka was three when forces

loyal to the teenaged Emperor Meiji put down the last vestiges of the Tokugawa

Shogunate. He had been born into a

samurai family near Kyoto, but a major plank in modernization was the abolition

of the Samurai class. Many former

samurai turned to the arts. Others

became foreign students, sent to the west to bring back modern thought and

technology. Kamisaka did both. After mastering Rimpa, he studied in Glasgow,

Scotland, and returned home to become the father of modern Japanese design.

Kamisaka considered Rimpa to be Japan’s

only native school of art, with all other styles coming first from China. Rimpa originated early in the 17th

Century, and could appear as hanging paintings, folding screens, decorative fans,

lacquer ware, textiles, ceramics, woodblock, or books of prints. Kamisaka worked in each of these. Backgrounds often bore calligraphy and a distinctive

gold or silver sheen, against which objects appeared in strong colors, sometimes with bold

outlines and other times with no outline at all. Subject matter often came from

plants, flowers, or birds, but sometimes came from legends, the theater, or popular stories. Because the patrons who supported it were wealthy, Rimpa exudes a stylized lavishness.

Kamisaka considered Rimpa to be Japan’s

only native school of art, with all other styles coming first from China. Rimpa originated early in the 17th

Century, and could appear as hanging paintings, folding screens, decorative fans,

lacquer ware, textiles, ceramics, woodblock, or books of prints. Kamisaka worked in each of these. Backgrounds often bore calligraphy and a distinctive

gold or silver sheen, against which objects appeared in strong colors, sometimes with bold

outlines and other times with no outline at all. Subject matter often came from

plants, flowers, or birds, but sometimes came from legends, the theater, or popular stories. Because the patrons who supported it were wealthy, Rimpa exudes a stylized lavishness. |

| Noh Scene: Hagoromo, Kamisaka Sekka (ca. 1920-1940) |

|

| Moon and Waves, Suzuki Kiitsu (1796-1858) |

Pieces by several of the earlier masters

caught my attention. Suzuki Kiitsu’s

Moon and Waves achieves wild excitement with very simple colors and lines, with

a modern appearance in stark contrast to my image of Tokugawa feudalism.

I enjoyed Kamisaka’s more traditional work, with less of a European influence. He was sent with the assignment to discover what Europeans would like to see in Japanese art. He accomplished the task well, but Edwardian tastes are not my tastes.

I enjoyed Kamisaka’s more traditional work, with less of a European influence. He was sent with the assignment to discover what Europeans would like to see in Japanese art. He accomplished the task well, but Edwardian tastes are not my tastes.

|

| Pages from “All Kinds of Things” (“Chigusa,”), Kamisaka Sekka (1903) |

A gentlemen saw me admiring Suzuki’s

Bush Clover and Pampas Grass and came to tell me he had enjoyed it for several

years, hanging in his bedroom. I asked

if he was Mr. Clark, and he corrected me, “Bill.” At that moment, we were interrupted by the

start of Dr. Marks’ talk, and we did not get to finish our conversation, but I

must point out that in three visits to the Victoria and Albert Museum, in

London, I have never yet been approached by either Victoria or Albert.

|

| Grasshopper detail from Autumn Grasses and Moon, Sakai Ōho (1808-1841) |

|

| Seven Lucky Gods, Kamisaka Sekka (ca. 1920-1930) |

|

| Morning Glories, Kamisaka Sekka (ca. 1920-1940) |

|

| Takasago, Kamisaka Sekka (ca. 1920-1930) |

I enjoy visiting the Clark Center. As a small museum, it has a special personality. After my previous visit—a samurai exhibit, I got too busy to post anything on this blog. Then, last summer I had the chance to see a similar presentation, in London. I came away impressed that the Clark had done a better job telling the samurai story than had the Victoria and Albert. The difference is, even if a visitor can devote most of one day to the Victoria and Albert, one still feels the pressure to race from item to item, running from antiquity to the present, and from continent to continent. There are thousands of things to see. Yet in the samurai room, the Victoria and Albert was outdone by the Clark. The Clark told a richer story, and gave visitors a more intimate setting.

|

| Samurai at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, July 2011 |

|

| Samurai at the Clark Center for Japanese Art and Culture, January, 2010 |

I may get back for a second look at the

Rimpa before it closes, July 28th.

Then I look forward to a two-part presentation of landscapes, beginning

in September.

For more on the Clark Center for Japanese Art and Culture:

For my previous review of the Clark Center for Japanese Art and Culture:

Posted by

Brian

at

12:23 AM

5

comments

Labels: Art, California, Europe, History, Japan, Museums, Photography, Plants and Flowers, Travel, Visalia

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

+Hekiba+Village+.JPG)